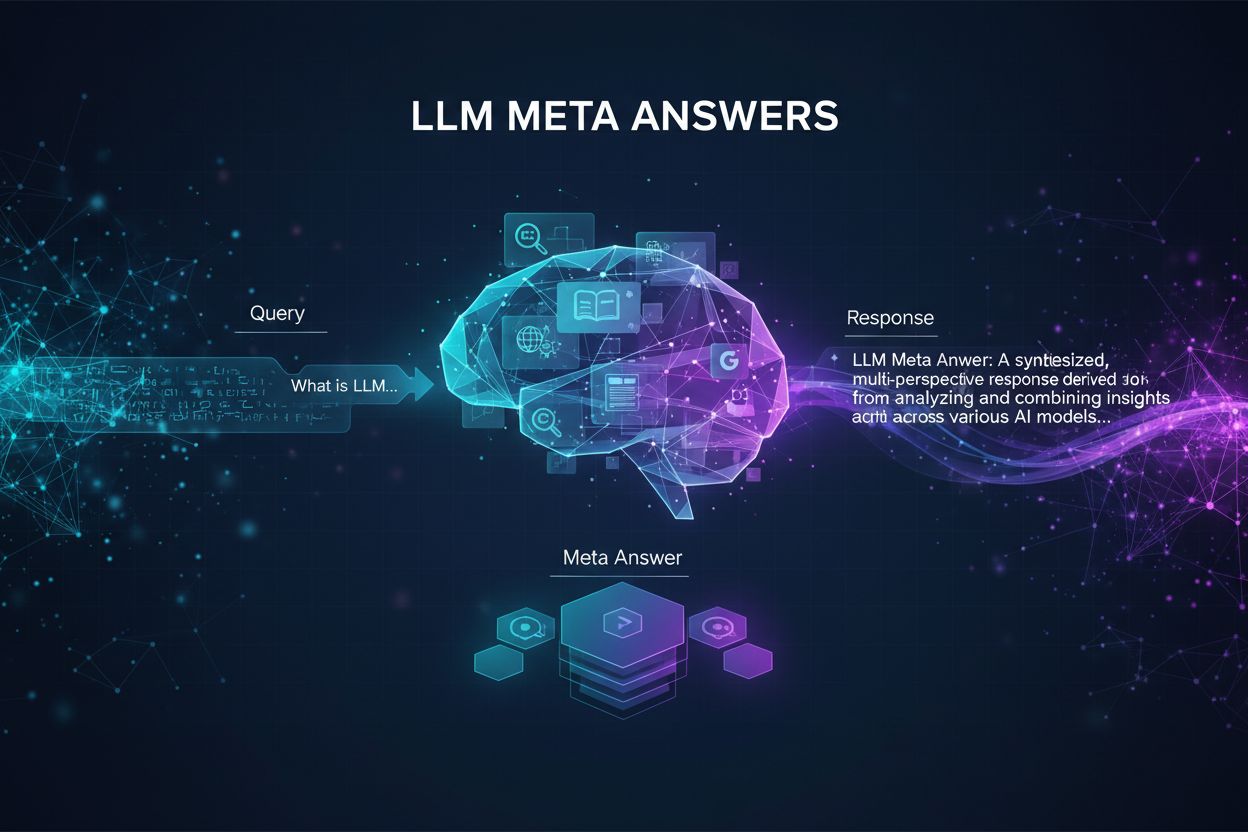

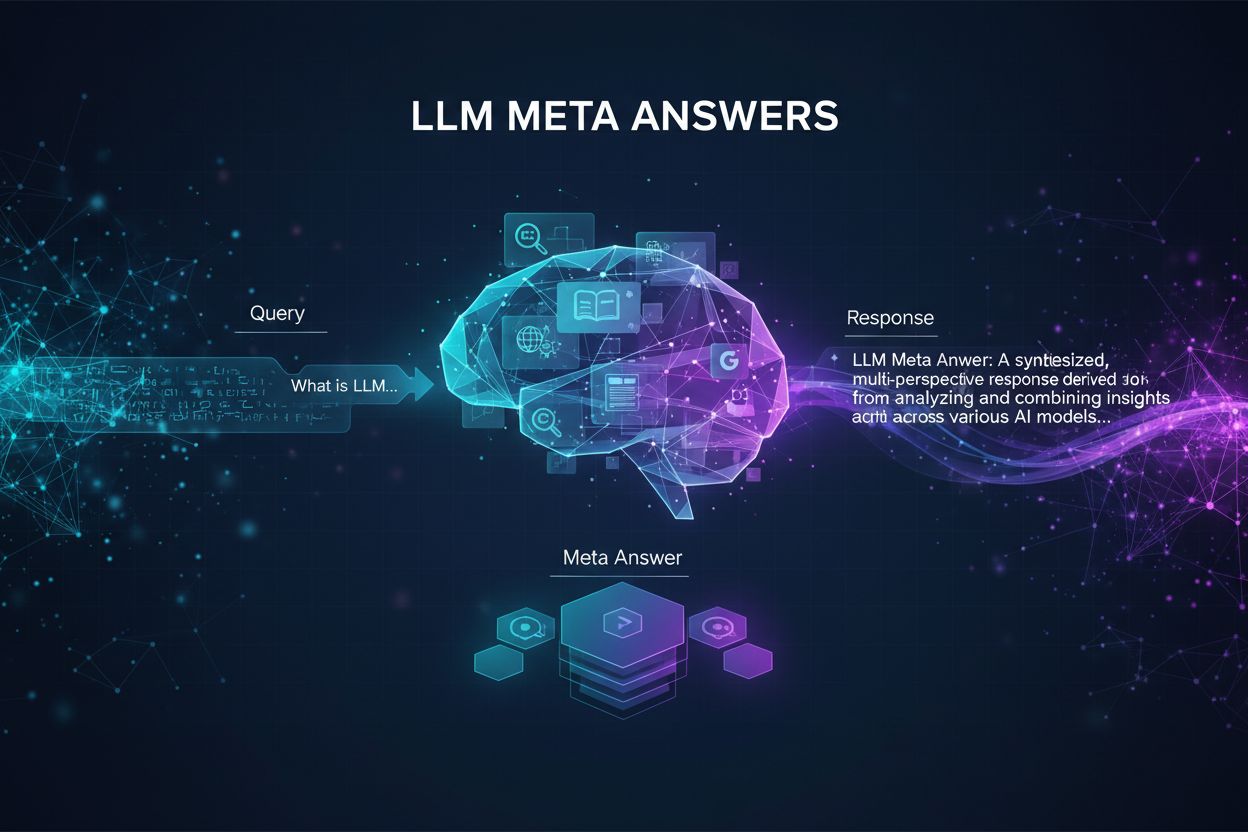

LLM Meta Answers

Learn what LLM Meta Answers are and how to optimize your content for visibility in AI-generated responses from ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews. Dis...

Discover how LLMs generate responses through tokenization, transformer architecture, attention mechanisms, and probabilistic prediction. Learn the technical process behind AI answer generation.

Large language models generate responses by converting input text into tokens, processing them through transformer layers using attention mechanisms, and predicting the next token based on learned patterns from billions of parameters. This process repeats iteratively until a complete response is generated.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Perplexity don’t retrieve pre-written answers from a database. Instead, they generate responses through a sophisticated process of pattern recognition and probabilistic prediction. When you submit a prompt, the model doesn’t “look up” information—it predicts what words or ideas should come next based on everything it learned during training. This fundamental distinction is crucial to understanding how modern AI systems work. The process involves multiple stages of transformation, from breaking down text into manageable pieces to processing them through billions of interconnected parameters. Each stage refines the model’s understanding and generates increasingly sophisticated representations of meaning.

The journey of response generation begins with tokenization, a process that converts raw text into discrete units called tokens. These tokens aren’t always complete words; they can be letters, syllables, subword units, or entire words depending on the tokenizer’s design. When you input “Explain how photosynthesis works,” the model breaks this down into tokens that it can process mathematically. For example, a sentence might be split into tokens like [“Explain”, “how”, “photo”, “synthesis”, “works”]. This tokenization is essential because neural networks operate on numerical data, not raw text. Each token is then mapped to a unique identifier that the model can work with. The tokenizer used by different LLMs varies—some use byte-pair encoding, others use different algorithms—but the goal remains consistent: converting human language into a format suitable for mathematical computation.

Once text is tokenized, each token is converted into a token embedding—a numerical vector that captures semantic and lexical information about that token. These embeddings are learned during training and exist in a high-dimensional space (often 768 to 12,288 dimensions). Tokens with similar meanings have embeddings that are close together in this space. For instance, the embeddings for “king” and “emperor” would be positioned near each other because they share semantic properties. However, at this stage, each token embedding only contains information about that individual token, not about its position in the sequence or its relationship to other tokens.

To address this limitation, the model applies positional encoding, which injects information about each token’s position in the sequence. This is typically done using trigonometric functions (sine and cosine waves) that create unique positional signatures for each location. This step is critical because the model needs to understand not just what words are present, but in what order they appear. The positional information is added to the token embedding, creating an enriched representation that encodes both “what the token is” and “where it sits in the sequence.” This combined representation then enters the core processing layers of the transformer.

The transformer architecture is the backbone of modern LLMs, introduced in the groundbreaking 2017 paper “Attention Is All You Need.” Unlike older sequential models like RNNs and LSTMs that processed information one token at a time, transformers can analyze all tokens in a sequence simultaneously. This parallel processing capability dramatically speeds up both training and inference. The transformer consists of multiple stacked layers, each containing two main components: multi-headed attention and feed-forward neural networks. These layers work together to progressively refine the model’s understanding of the input text.

| Component | Function | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Tokenization | Converts text to discrete units | Enable mathematical processing |

| Token Embedding | Maps tokens to numerical vectors | Capture semantic meaning |

| Positional Encoding | Adds position information | Preserve sequence order |

| Multi-Head Attention | Weighs relationships between tokens | Understand context and dependencies |

| Feed-Forward Networks | Refines token representations | Extract higher-level patterns |

| Output Projection | Converts to probability distribution | Generate next token |

Multi-headed attention is arguably the most important component in the transformer architecture. It allows the model to simultaneously focus on different aspects of the input text. Each “head” operates independently with its own set of learned weight matrices, enabling the model to capture different types of linguistic relationships. For example, one attention head might specialize in capturing grammatical relationships, another in semantic meanings, and a third in syntactic patterns.

The attention mechanism works through three key vectors for each token: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V). The Query vector represents the current token asking “what should I pay attention to?” The Key vectors represent all tokens in the sequence, answering “here’s what I am.” The model calculates attention scores by computing the dot product between the Query and Key vectors, which measures how relevant each token is to the current position. These scores are then normalized using softmax, which converts them into attention weights that sum to one. Finally, the model computes a weighted sum of the Value vectors using these attention weights, producing a context-enriched representation for each token.

Consider the sentence “The CEO told the manager that she would approve the deal.” The attention mechanism must determine that “she” refers to the CEO, not the manager. The Query vector for “she” will have high attention weights for “CEO” because the model has learned that pronouns typically refer to subjects. This ability to resolve ambiguity and understand long-range dependencies is what makes attention mechanisms so powerful. Multiple attention heads working in parallel allow the model to capture this information while simultaneously attending to other linguistic patterns.

After the attention mechanism processes each token, the output passes through feed-forward neural networks (FFNs). These are relatively simple multilayer perceptrons applied independently to each token. While attention mixes information across all tokens in the sequence, the FFN step refines the contextual patterns that attention has already integrated. The FFN layers extract higher-level features and patterns from the attention output, further enriching each token’s representation.

Both the attention and FFN components use residual connections and layer normalization. Residual connections allow information to flow directly from one layer to the next, preventing information loss in deep networks. Layer normalization stabilizes the training process by normalizing the outputs of each layer. These techniques ensure that as information flows through many layers (modern LLMs have 12 to 96+ layers), the representations remain coherent and meaningful. Each layer progressively enriches the token embeddings with more abstract, higher-level linguistic information.

The transformer processes input through multiple stacked layers, with each layer refining the token representations. In the first layer, tokens gain awareness of their immediate context and relationships with nearby tokens. As information flows through subsequent layers, tokens develop increasingly sophisticated understanding of long-range dependencies, semantic relationships, and abstract concepts. A token’s representation at layer 50 in a 96-layer model contains vastly more contextual information than its representation at layer 1.

This iterative refinement is crucial for understanding complex linguistic phenomena. Early layers might capture basic syntactic patterns, middle layers might identify semantic relationships, and later layers might understand abstract concepts and reasoning patterns. The model doesn’t explicitly learn these hierarchies—they emerge naturally from the training process. By the time a token reaches the final layer, its representation encodes not just its literal meaning, but its role in the entire input sequence and how it relates to the task at hand.

After processing through all transformer layers, each token has a final representation that captures rich contextual information. However, the model’s ultimate goal is to generate the next token in the sequence. To accomplish this, the final token representation (typically the last token in the input sequence) is projected through a linear output layer followed by a softmax function.

The linear output layer multiplies the final token representation by a weight matrix to produce logits—unnormalized scores for each token in the vocabulary. These logits indicate the model’s raw preference for each possible next token. The softmax function then converts these logits into a probability distribution where all probabilities sum to one. This probability distribution represents the model’s assessment of which token should come next. For example, if the input is “The sky is,” the model might assign high probability to “blue” and lower probabilities to other colors or unrelated words.

Once the model produces a probability distribution over the vocabulary, it must select which token to generate. The simplest approach is greedy decoding, which always selects the token with the highest probability. However, this can lead to repetitive or suboptimal responses. More sophisticated approaches include temperature sampling, which adjusts the probability distribution to make it more or less uniform, and top-k sampling, which only considers the k most likely tokens. Beam search maintains multiple candidate sequences and selects the overall best one based on cumulative probability.

The selected token is then appended to the input sequence, and the entire process repeats. The model processes the original input plus the newly generated token, producing a probability distribution for the next token. This iterative process continues until the model generates a special end-of-sequence token or reaches a maximum length limit. This is why LLM responses are generated token-by-token, with each new token depending on all previous tokens in the sequence.

The remarkable capabilities of LLMs stem from training on billions of tokens from diverse sources: books, articles, code repositories, conversations, and web pages. During training, the model learns to predict the next token given all previous tokens. This simple objective, repeated billions of times across massive datasets, causes the model to absorb patterns about language, facts, reasoning, and even coding. The model doesn’t memorize specific sentences; instead, it learns statistical patterns about how language works.

Modern LLMs contain billions to hundreds of billions of parameters—adjustable weights that encode learned patterns. These parameters are refined through a process called backpropagation, where the model’s predictions are compared to actual next tokens, and errors are used to update the parameters. The scale of this training process is enormous: training a large model can require weeks or months on specialized hardware and consume massive amounts of electricity. However, once trained, the model can generate responses in milliseconds.

Raw language model training produces models that can generate fluent text but may produce inaccurate, biased, or harmful content. To address this, developers apply fine-tuning and alignment techniques. Fine-tuning involves training the model on curated datasets of high-quality examples. Alignment involves having human experts rate model outputs and using this feedback to further refine the model through techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

These post-training processes teach the model to be more helpful, harmless, and honest. They don’t change the fundamental response generation mechanism but rather guide the model toward generating better responses. This is why different LLMs (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) produce different outputs for the same prompt—they’ve been fine-tuned and aligned differently. The human touch in this process is essential; without alignment, LLMs would be less useful and potentially harmful.

LLMs generate responses that feel remarkably human-like because they’ve learned from billions of examples of human communication. The model has absorbed patterns about how humans structure arguments, express emotions, use humor, and adapt tone to context. When you ask an LLM for encouragement, it doesn’t consciously decide to be empathetic—rather, it has learned that certain response patterns follow encouraging prompts in its training data.

This learned understanding of conversational dynamics, combined with the attention mechanism’s ability to maintain context, creates responses that feel coherent and contextually appropriate. The model can maintain consistent character, remember earlier parts of a conversation, and adjust its tone based on the user’s apparent needs. These capabilities emerge from the statistical patterns learned during training, not from explicit programming. This is why LLMs can engage in nuanced conversations, understand subtle implications, and generate creative content.

Despite their sophistication, LLMs have important limitations. They can only process a limited amount of context at once, defined by the context window (typically 2,000 to 200,000 tokens depending on the model). Information beyond this window is lost. Additionally, LLMs don’t have real-time access to current information; they can only work with knowledge from their training data. They can hallucinate—confidently generating false information that sounds plausible. They also struggle with tasks requiring precise mathematical calculation or logical reasoning that goes beyond pattern matching.

Understanding these limitations is crucial for effectively using LLMs. They excel at tasks involving language understanding, generation, and pattern recognition but should be combined with other tools for tasks requiring real-time information, precise computation, or guaranteed accuracy. As LLM technology evolves, researchers are developing techniques like retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which allows models to access external information sources, and chain-of-thought prompting, which encourages step-by-step reasoning.

Track how your brand, domain, and URLs appear in AI answers across ChatGPT, Perplexity, and other AI search engines. Stay informed about your presence in AI-generated responses.

Learn what LLM Meta Answers are and how to optimize your content for visibility in AI-generated responses from ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews. Dis...

Learn how to optimize content for AI summarization across ChatGPT, Perplexity, Google AI Overviews, and Claude. Master semantic HTML, passage-level optimization...

Learn what generative engines are, how they differ from traditional search, and their impact on ChatGPT, Perplexity, Google AI Overviews, and Claude. Complete g...