Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanism is a machine learning technique that directs deep learning models to prioritize relevant input data parts. Learn how it powers transformers,...

Model parameters are learnable variables within AI models, such as weights and biases, that are automatically adjusted during training to optimize the model’s ability to make accurate predictions and define how the model processes input data to generate outputs.

Model parameters are learnable variables within AI models, such as weights and biases, that are automatically adjusted during training to optimize the model's ability to make accurate predictions and define how the model processes input data to generate outputs.

Model parameters are learnable variables within artificial intelligence models that are automatically adjusted during the training process to optimize the model’s ability to make accurate predictions and define how the model processes input data to generate outputs. These parameters serve as the fundamental “control knobs” of machine learning systems, determining the precise behavior and decision-making patterns of AI models. In the context of deep learning and neural networks, parameters primarily consist of weights and biases—numerical values that control how information flows through the network and how strongly different features influence predictions. The purpose of training is to discover the optimal values for these parameters that minimize prediction errors and enable the model to generalize well to new, unseen data. Understanding model parameters is essential for comprehending how modern AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews function and why they produce different outputs for the same input.

The concept of learnable parameters in machine learning dates back to the early days of artificial neural networks in the 1950s and 1960s, when researchers first recognized that networks could adjust internal values to learn from data. However, the practical application of parameters remained limited until the advent of backpropagation in the 1980s, which provided an efficient algorithm for computing how to adjust parameters to reduce errors. The explosion of parameter counts accelerated dramatically with the rise of deep learning in the 2010s. Early convolutional neural networks for image recognition contained millions of parameters, while modern large language models (LLMs) contain hundreds of billions or even trillions of parameters. According to research from Our World in Data and Epoch AI, the parameter count in notable AI systems has grown exponentially, with GPT-3 containing 175 billion parameters, GPT-4o containing approximately 200 billion parameters, and some estimates suggesting GPT-4 may contain up to 1.8 trillion parameters when accounting for mixture-of-experts architectures. This dramatic scaling has fundamentally transformed what AI systems can accomplish, enabling them to capture increasingly complex patterns in language, vision, and reasoning tasks.

Model parameters operate through a mathematical framework where each parameter represents a numerical value that influences how the model transforms inputs into outputs. In a simple linear regression model, parameters consist of the slope (m) and intercept (b) in the equation y = mx + b, where these two values determine the line that best fits the data. In neural networks, the situation becomes exponentially more complex. Each neuron in a layer receives inputs from the previous layer, multiplies each input by a corresponding weight parameter, sums these weighted inputs, adds a bias parameter, and passes the result through an activation function to produce an output. This output then becomes input to neurons in the next layer, creating a cascading chain of parameter-driven transformations. During training, the model uses gradient descent and related optimization algorithms to compute how each parameter should be adjusted to reduce the loss function—a mathematical measure of prediction error. The gradient of the loss with respect to each parameter indicates the direction and magnitude of adjustment needed. Through backpropagation, these gradients flow backward through the network, allowing the optimizer to update all parameters simultaneously in a coordinated manner. This iterative process continues across multiple training epochs until the parameters converge to values that minimize loss on the training data while maintaining good generalization to new data.

| Aspect | Model Parameters | Hyperparameters | Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Learnable variables adjusted during training | Configuration settings defined before training | Input data characteristics used by the model |

| When Set | Automatically learned through optimization | Manually configured by practitioners | Extracted or engineered from raw data |

| Examples | Weights, biases in neural networks | Learning rate, batch size, number of layers | Pixel values in images, word embeddings in text |

| Impact on Model | Determine how model maps inputs to outputs | Control the training process and model structure | Provide the raw information model learns from |

| Optimization Method | Gradient descent, Adam, AdaGrad | Grid search, random search, Bayesian optimization | Feature engineering, feature selection |

| Number in Large Models | Billions to trillions (e.g., 200B in GPT-4o) | Typically 5-20 key hyperparameters | Thousands to millions depending on data |

| Computational Cost | High during training; impacts inference speed | Minimal computational cost to set | Determined by data collection and preprocessing |

| Transferability | Can be transferred via fine-tuning and transfer learning | Must be retuned for new tasks | May require re-engineering for new domains |

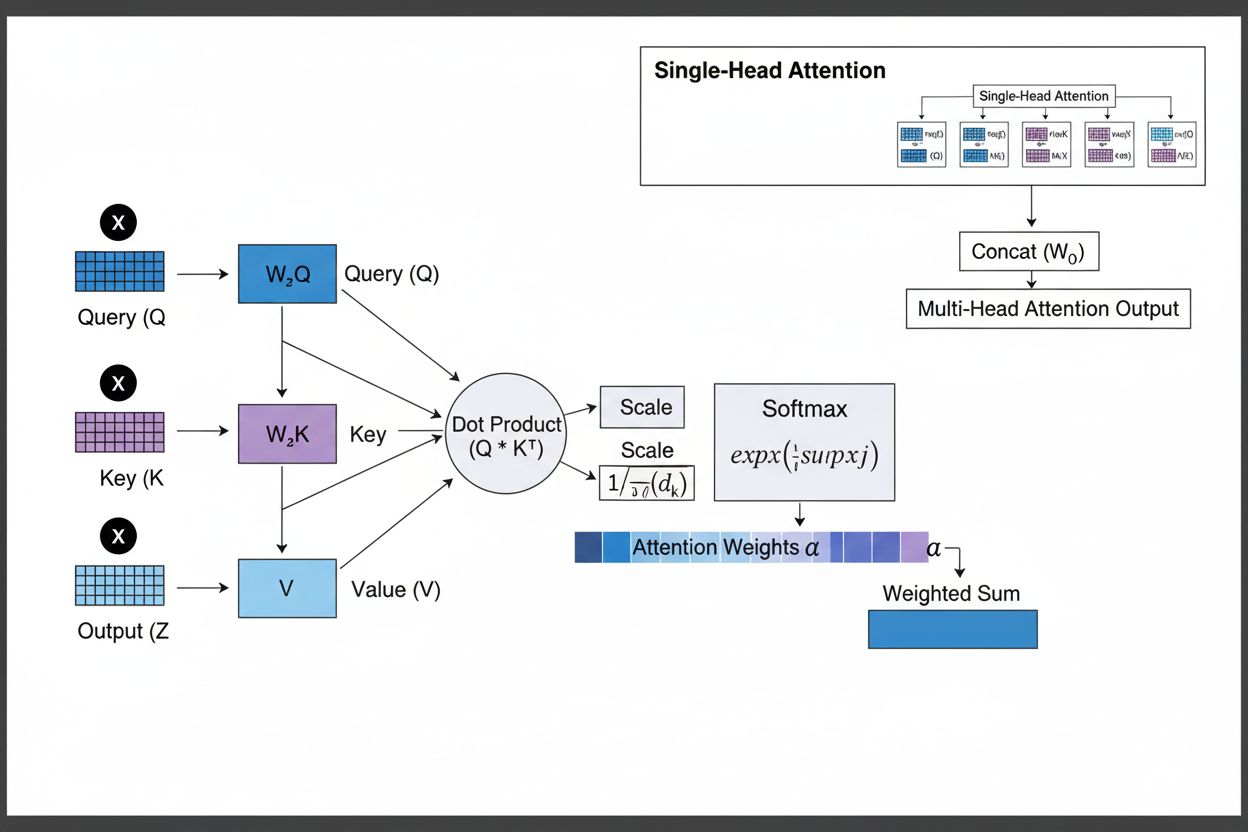

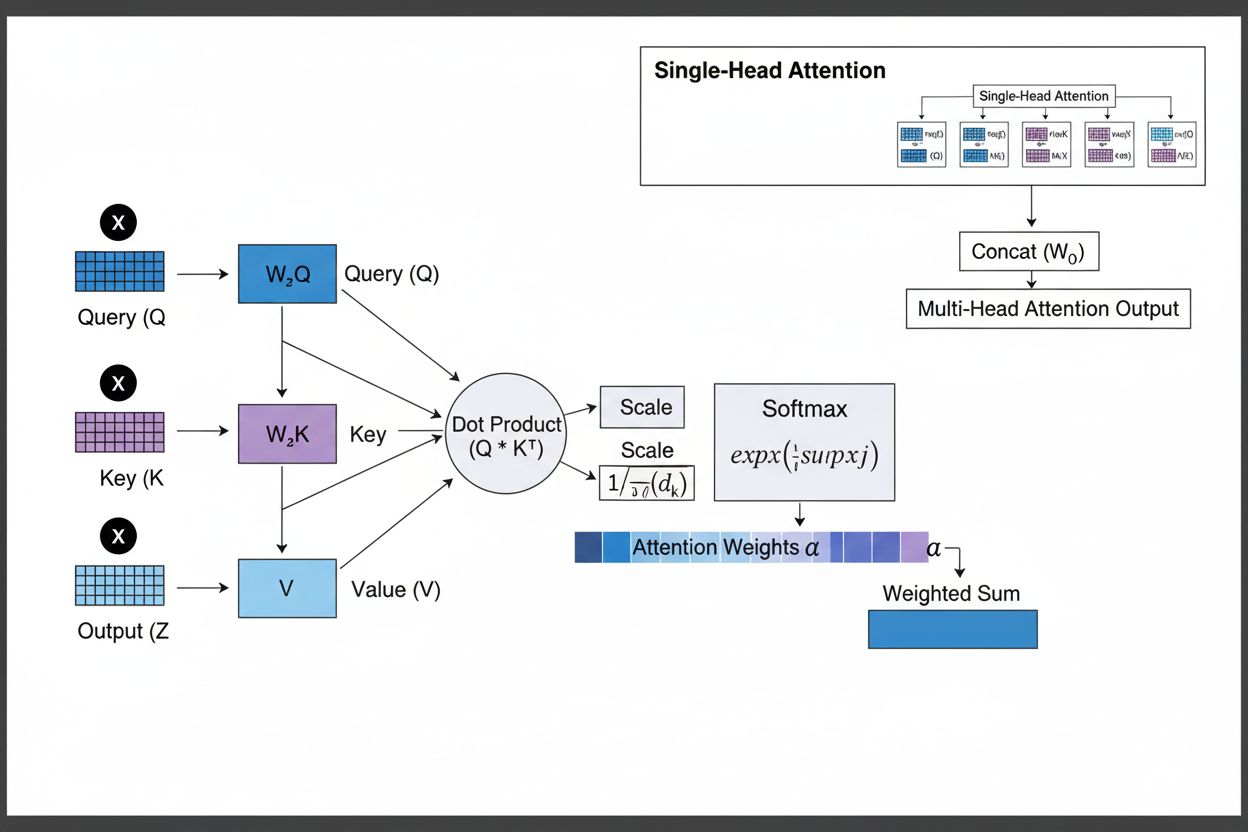

Model parameters take different forms depending on the architecture and type of machine learning model being used. In convolutional neural networks (CNNs) used for image recognition, parameters include the weights in convolutional filters (also called kernels) that detect spatial patterns like edges, textures, and shapes at different scales. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks contain parameters that control information flow through time, including gating parameters that determine what information to remember or forget. Transformer models, which power modern large language models, contain parameters in multiple components: attention weights that determine which parts of the input to focus on, feed-forward network weights, and layer normalization parameters. In probabilistic models like Naive Bayes, parameters define conditional probability distributions. Support vector machines use parameters that position and orient decision boundaries in feature space. Mixture of Experts (MoE) models, used in some versions of GPT-4, contain parameters for multiple specialized sub-networks plus routing parameters that determine which experts process each input. This architectural diversity means that the nature and number of parameters varies significantly across different model types, but the fundamental principle remains constant: parameters are the learned values that enable the model to perform its task.

Weights and biases represent the two fundamental types of parameters in neural networks and form the foundation of how these models learn. Weights are numerical values assigned to connections between neurons, determining the strength and direction of influence that one neuron’s output has on the next neuron’s input. In a fully connected layer with 1,000 input neurons and 500 output neurons, there would be 500,000 weight parameters—one for each connection. During training, weights are adjusted to increase or decrease the influence of specific features on predictions. A large positive weight means that feature strongly activates the next neuron, while a negative weight inhibits it. Biases are additional parameters, one per neuron in a layer, that provide a constant offset to the neuron’s input sum before the activation function is applied. Mathematically, if a neuron receives weighted inputs that sum to zero, the bias allows the neuron to still produce a non-zero output, providing crucial flexibility. This flexibility enables neural networks to learn complex decision boundaries and capture patterns that wouldn’t be possible with weights alone. In a model with 200 billion parameters like GPT-4o, the vast majority are weights in the attention mechanisms and feed-forward networks, with biases comprising a smaller but still significant portion. Together, weights and biases enable the model to learn the intricate patterns in language, vision, or other domains that make modern AI systems so powerful.

The number of parameters in a model has a profound impact on its capability to learn complex patterns and its overall performance. Research consistently shows that scaling laws govern the relationship between parameter count, training data size, and model performance. Models with more parameters can represent more complex functions and capture more nuanced patterns in data, generally leading to better performance on challenging tasks. GPT-3 with 175 billion parameters demonstrated remarkable few-shot learning abilities that smaller models couldn’t match. GPT-4o with 200 billion parameters shows further improvements in reasoning, code generation, and multimodal understanding. However, the relationship between parameters and performance is not linear and depends critically on the amount and quality of training data. A model with too many parameters relative to training data will overfit, memorizing specific examples rather than learning generalizable patterns, resulting in poor performance on new data. Conversely, a model with too few parameters may underfit, failing to capture important patterns and achieving suboptimal performance even on training data. The optimal parameter count for a given task depends on factors including the complexity of the task, the size and diversity of the training dataset, and computational constraints. Research from Epoch AI shows that modern AI systems have achieved remarkable performance through massive scaling, with some models containing trillions of parameters when accounting for mixture-of-experts architectures where not all parameters are active for every input.

While large models with billions of parameters achieve impressive performance, the computational cost of training and deploying such models is substantial. This has driven research into parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods that allow practitioners to adapt pre-trained models to new tasks without updating all parameters. LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) is a prominent technique that freezes most pre-trained parameters and only trains a small set of additional low-rank matrices, reducing the number of trainable parameters by orders of magnitude while maintaining performance. For example, fine-tuning a 7 billion parameter model with LoRA might involve training only 1-2 million additional parameters rather than all 7 billion. Adapter modules insert small trainable networks between layers of a frozen pre-trained model, adding only a small percentage of parameters while enabling task-specific adaptation. Prompt engineering and in-context learning represent alternative approaches that don’t modify parameters at all, instead using the model’s existing parameters more effectively through carefully crafted inputs. These parameter-efficient approaches have democratized access to large language models, enabling organizations with limited computational resources to customize state-of-the-art models for their specific needs. The trade-off between parameter efficiency and performance remains an active area of research, with practitioners balancing the desire for computational efficiency against the need for task-specific accuracy.

Understanding model parameters is crucial for platforms like AmICited that monitor how brands and domains appear in AI-generated responses across systems like ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, and Google AI Overviews. Different AI models with different parameter configurations produce different outputs for the same query, influencing where and how brands are mentioned. The 200 billion parameters in GPT-4o are configured differently than the parameters in Claude 3.5 Sonnet or Perplexity’s models, leading to variations in response generation. Parameters learned during training on different datasets and with different training objectives cause models to have different knowledge, reasoning patterns, and citation behaviors. When monitoring brand mentions in AI responses, understanding that these differences stem from parameter variations helps explain why a brand might be prominently featured in one AI system’s response but barely mentioned in another’s. The parameters that control attention mechanisms determine which parts of the model’s training data are most relevant to a query, influencing citation patterns. Parameters in the output generation layers determine how the model structures and presents information. By tracking how different AI systems with different parameter configurations mention brands, AmICited provides insights into how parameter-driven model behavior affects brand visibility in the AI-powered search landscape.

The future of model parameters is being shaped by several converging trends that will fundamentally alter how AI systems are designed and deployed. Mixture of Experts (MoE) architectures represent a significant evolution, where models contain multiple specialized sub-networks (experts) with separate parameters, and a routing mechanism determines which experts process each input. This approach allows models to scale to trillions of parameters while maintaining computational efficiency during inference, since not all parameters are active for every input. GPT-4 reportedly uses a MoE architecture with 16 experts, each containing 110 billion parameters, totaling 1.8 trillion parameters but using only a fraction during inference. Sparse parameters and pruning techniques are being developed to identify and remove less important parameters, reducing model size without sacrificing performance. Continual learning approaches aim to update parameters efficiently as new data becomes available, enabling models to adapt without full retraining. Federated learning distributes parameter training across multiple devices while preserving privacy, allowing organizations to benefit from large-scale training without centralizing sensitive data. The emergence of small language models (SLMs) with billions rather than hundreds of billions of parameters suggests a future where parameter efficiency becomes as important as raw parameter count. As AI systems become more integrated into critical applications, understanding and controlling model parameters will become increasingly important for ensuring safety, fairness, and alignment with human values. The relationship between parameter count and model behavior will continue to be a central focus of AI research, with implications for everything from computational sustainability to the interpretability and trustworthiness of AI systems.

Model parameters are internal variables learned during training through optimization algorithms like gradient descent, while hyperparameters are external settings configured before training begins. Parameters determine how the model maps inputs to outputs, whereas hyperparameters control the training process itself, such as learning rate and number of epochs. For example, weights and biases in neural networks are parameters, while the learning rate is a hyperparameter.

Modern large language models contain billions to trillions of parameters. GPT-4o contains approximately 200 billion parameters, while GPT-4o-mini has about 8 billion parameters. Claude 3.5 Sonnet also operates with hundreds of billions of parameters. These massive parameter counts enable these models to capture complex patterns in language and generate sophisticated, contextually relevant responses across diverse topics.

More parameters increase a model's capacity to learn complex patterns and relationships in data. With additional parameters, models can represent more nuanced features and interactions, leading to higher accuracy on training data. However, there's a critical balance: too many parameters relative to training data can cause overfitting, where the model memorizes noise rather than learning generalizable patterns, resulting in poor performance on new, unseen data.

Model parameters are updated through backpropagation and optimization algorithms like gradient descent. During training, the model makes predictions, calculates the loss (error) between predictions and actual values, and then computes gradients showing how each parameter contributed to that error. The optimizer then adjusts parameters in the direction that reduces loss, repeating this process across multiple training iterations until the model converges to optimal values.

Weights determine the strength of connections between neurons in neural networks, controlling how strongly input features influence outputs. Biases act as threshold adjusters, allowing neurons to activate even when weighted inputs are zero, providing flexibility and enabling the model to learn baseline patterns. Together, weights and biases form the core learnable parameters that enable neural networks to approximate complex functions and make accurate predictions.

Model parameters directly influence how AI systems like ChatGPT, Perplexity, and Claude process and respond to queries. Understanding parameter counts and configurations helps explain why different AI models produce different outputs for the same prompt. For brand monitoring platforms like AmICited, tracking how parameters influence model behavior is crucial for predicting where brands appear in AI responses and understanding consistency across different AI systems.

Yes, through transfer learning, parameters from a pre-trained model can be adapted for new tasks. This approach, called fine-tuning, involves taking a model with learned parameters and adjusting them on new data for specific applications. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) allow selective parameter updates, reducing computational costs while maintaining performance. This technique is widely used to customize large language models for specialized domains.

Model parameters directly impact computational requirements during both training and inference. More parameters require more memory, processing power, and time to train and deploy. A model with 175 billion parameters (like GPT-3) demands significantly more computational resources than a 7 billion parameter model. This relationship is critical for organizations deploying AI systems, as parameter count influences infrastructure costs, latency, and energy consumption in production environments.

Start tracking how AI chatbots mention your brand across ChatGPT, Perplexity, and other platforms. Get actionable insights to improve your AI presence.

Attention mechanism is a machine learning technique that directs deep learning models to prioritize relevant input data parts. Learn how it powers transformers,...

Learn what perplexity score means in content and language models. Understand how it measures model uncertainty, prediction accuracy, and text quality evaluation...

Perplexity Score measures text predictability in language models. Learn how this key NLP metric quantifies model uncertainty, its calculation, applications, and...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.