Token Limits and Content Optimization: Technical Considerations

Explore how token limits affect AI performance and learn practical strategies for content optimization including RAG, chunking, and summarization techniques.

A token is the basic unit of text processed by language models, representing words, subwords, characters, or punctuation marks converted into numerical identifiers. Tokens form the foundation of how AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity understand and generate text, with each token assigned a unique integer value within the model’s vocabulary.

A token is the basic unit of text processed by language models, representing words, subwords, characters, or punctuation marks converted into numerical identifiers. Tokens form the foundation of how AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity understand and generate text, with each token assigned a unique integer value within the model's vocabulary.

A token is the fundamental unit of text that language models process and understand. Tokens represent words, subwords, character sequences, or punctuation marks, each assigned a unique numerical identifier within the model’s vocabulary. Rather than processing raw text directly, AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews convert all input text into sequences of tokens—essentially translating human language into a numerical format that neural networks can compute. This tokenization process is the critical first step that enables language models to analyze semantic relationships, generate coherent responses, and maintain computational efficiency. Understanding tokens is essential for anyone working with AI systems, as token counts directly influence API costs, response quality, and the model’s ability to maintain context across conversations.

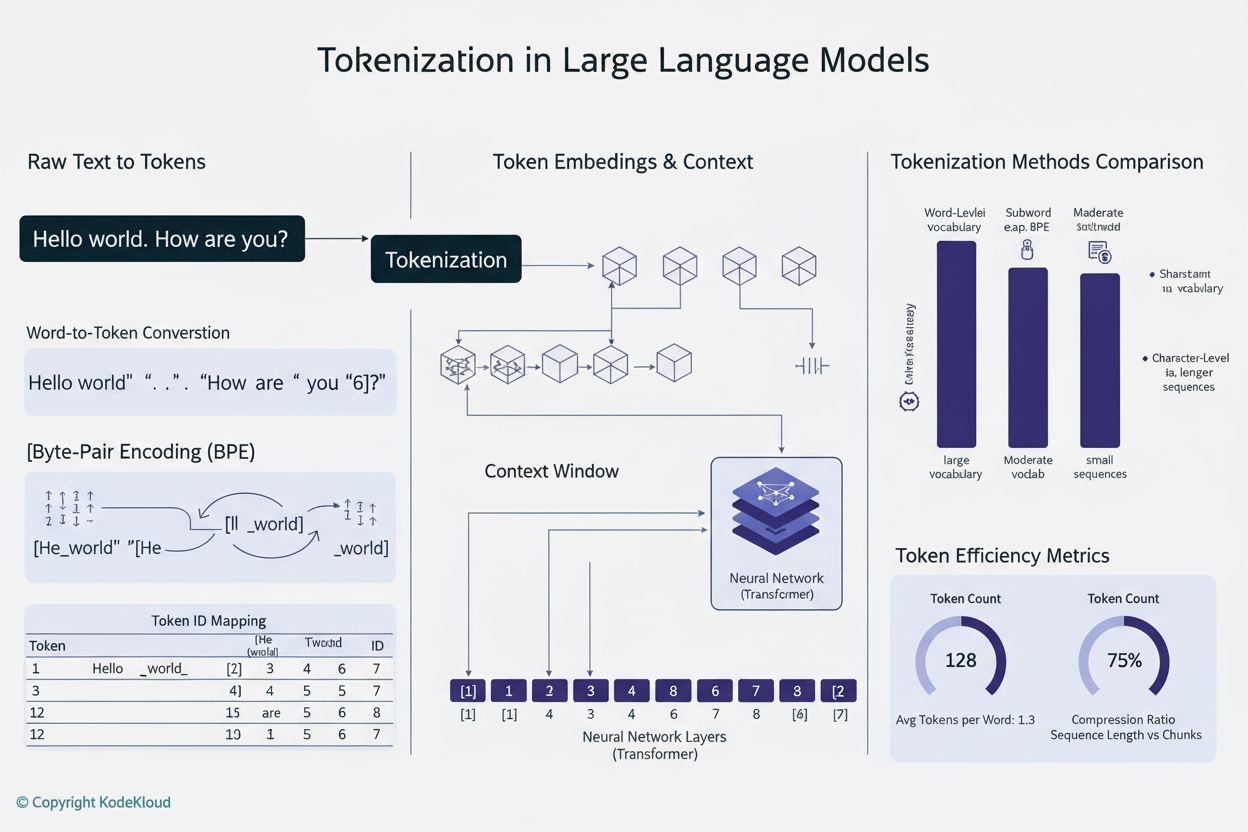

Tokenization is the systematic process of breaking down raw text into discrete tokens that a language model can process. When you input text into an AI system, the tokenizer first analyzes the text and splits it into manageable units. For example, the sentence “I heard a dog bark loudly” might be tokenized into individual tokens: I, heard, a, dog, bark, loudly. Each token then receives a unique numerical identifier—perhaps I becomes token ID 1, heard becomes 2, a becomes 3, and so forth. This numerical representation allows the neural network to perform mathematical operations on the tokens, calculating relationships and patterns that enable the model to understand meaning and generate appropriate responses.

The specific way text is tokenized depends on the tokenization algorithm employed by each model. Different language models use different tokenizers, which is why the same text can produce varying token counts across platforms. The tokenizer’s vocabulary—the complete set of unique tokens it recognizes—typically ranges from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of tokens. When the tokenizer encounters text it hasn’t seen before or words outside its vocabulary, it applies specific strategies to handle these cases, either breaking them into smaller subword tokens or representing them as combinations of known tokens. This flexibility is crucial for handling diverse languages, technical jargon, typos, and novel word combinations that appear in real-world text.

Different tokenization approaches offer distinct advantages and trade-offs. Understanding these methods is essential for comprehending how various AI platforms process information differently:

| Tokenization Method | How It Works | Advantages | Disadvantages | Used By |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word-Level | Splits text into complete words based on spaces and punctuation | Simple to understand; preserves full word meaning; smaller token sequences | Large vocabulary size; cannot handle unknown or rare words (OOV); inflexible with typos | Traditional NLP systems |

| Character-Level | Treats every individual character as a token, including spaces | Handles all possible text; no out-of-vocabulary issues; fine-grained control | Very long token sequences; requires more computation; low semantic density per token | Some specialized models; Chinese language models |

| Subword-Level (BPE) | Iteratively merges frequent character/subword pairs into larger tokens | Balances vocabulary size and coverage; handles rare words effectively; reduces OOV errors | More complex implementation; may split meaningful units; requires training | GPT models, ChatGPT, Claude |

| WordPiece | Starts with characters and progressively merges frequent combinations | Excellent for handling unknown words; efficient vocabulary; good semantic preservation | Requires pre-training; more computationally intensive | BERT, Google models |

| SentencePiece | Language-agnostic method treating text as raw bytes | Excellent for multilingual models; handles any Unicode character; no preprocessing needed | Less intuitive; requires specialized tools | Multilingual models, T5 |

Once text is converted into tokens, language models process these numerical sequences through multiple layers of neural networks. Each token is represented as a multi-dimensional vector called an embedding, which captures semantic meaning and contextual relationships. During the training phase, the model learns to recognize patterns in how tokens appear together, understanding that certain tokens frequently co-occur or appear in similar contexts. For instance, the tokens for “king” and “queen” develop similar embeddings because they share semantic properties, while “king” and “paper” have more distant embeddings due to their different meanings and usage patterns.

The model’s attention mechanism is crucial to this process. Attention allows the model to weigh the importance of different tokens relative to each other when generating a response. When processing the sentence “The bank executive sat by the river bank,” the attention mechanism helps the model understand that the first “bank” refers to a financial institution while the second “bank” refers to a riverbank, based on contextual tokens like “executive” and “river.” This contextual understanding emerges from the model’s learned relationships between token embeddings, enabling sophisticated language comprehension that goes far beyond simple word matching.

During inference (when the model generates responses), it predicts the next token in a sequence based on all previous tokens. The model calculates probability scores for every token in its vocabulary, then selects the most likely next token. This process repeats iteratively—the newly generated token is added to the sequence, and the model uses this expanded context to predict the following token. This token-by-token generation continues until the model predicts a special “end of sequence” token or reaches the maximum token limit. This is why understanding token limits is critical: if your prompt and desired response together exceed the model’s context window, the model cannot generate a complete response.

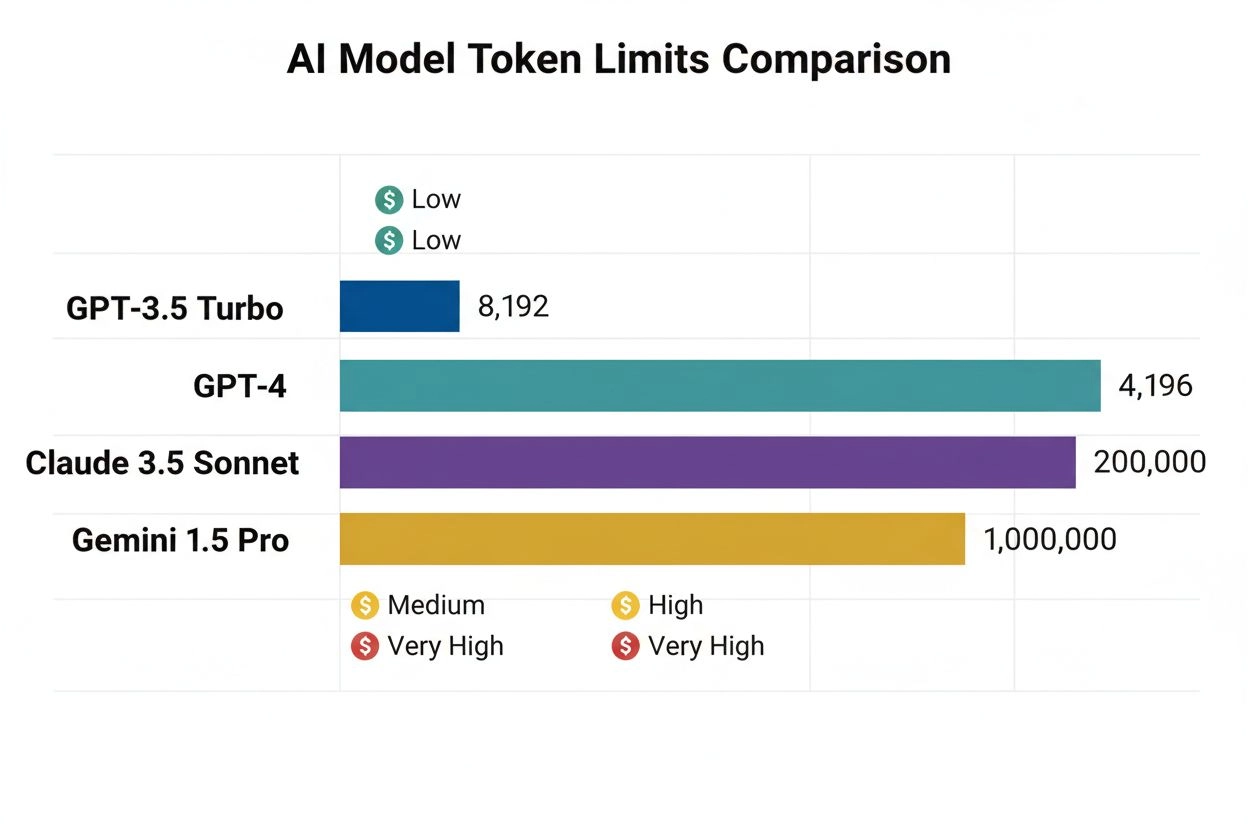

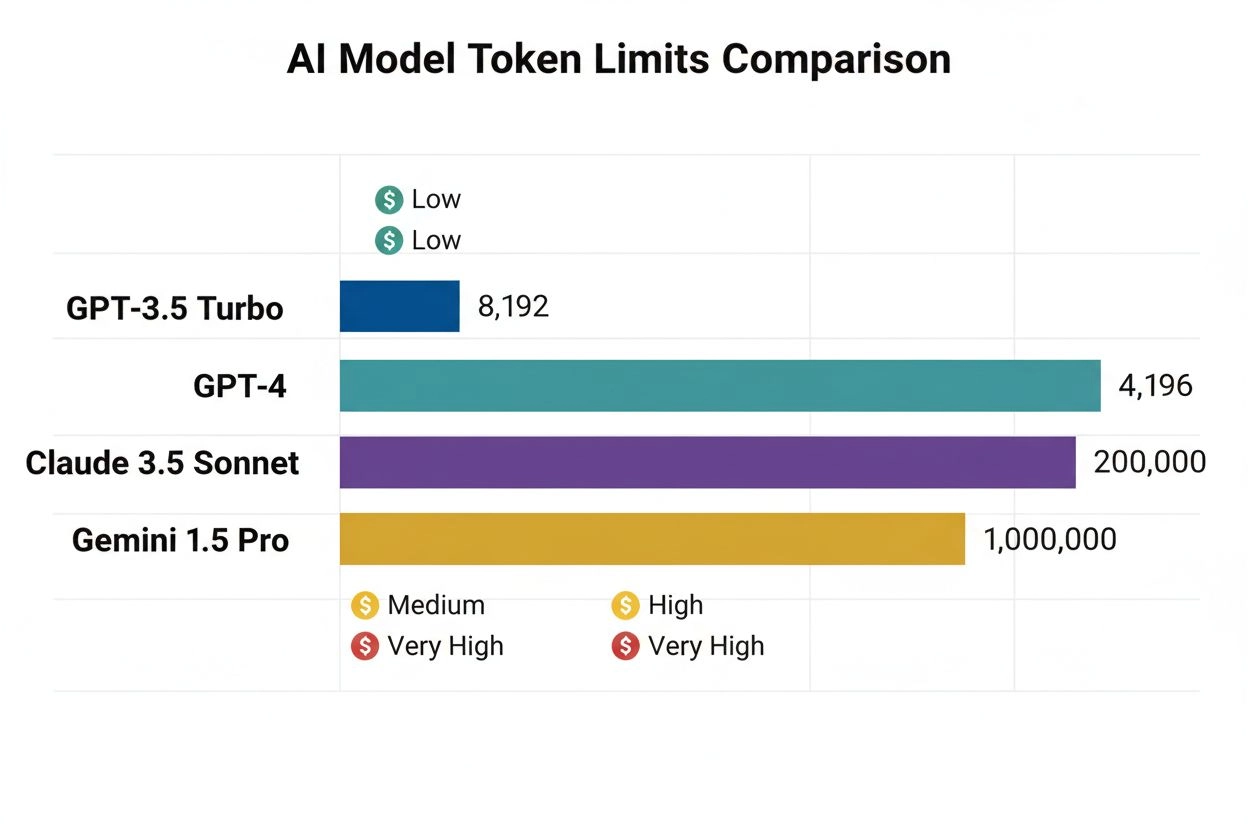

Every language model has a context window—a maximum number of tokens it can process simultaneously. This limit combines both input tokens (your prompt) and output tokens (the model’s response). For example, GPT-3.5-Turbo has a context window of 4,096 tokens, while GPT-4 offers windows ranging from 8,000 to 128,000 tokens depending on the version. Claude 3 models support context windows up to 200,000 tokens, enabling analysis of entire books or extensive documents. Understanding your model’s context window is essential for planning prompts and managing token budgets effectively.

Token counting tools are essential for optimizing AI usage. OpenAI provides the tiktoken library, an open-source tokenizer that allows developers to count tokens before making API calls. This prevents unexpected costs and enables precise prompt optimization. For example, if you’re using GPT-4 with an 8,000-token context window and your prompt uses 2,000 tokens, you have 6,000 tokens available for the model’s response. Knowing this constraint helps you craft prompts that fit within available token space while still requesting comprehensive responses. Different models use different tokenizers—Claude uses its own tokenization system, Perplexity implements its own approach, and Google AI Overviews uses yet another method. This variation means the same text produces different token counts across platforms, making platform-specific token counting essential for accurate cost estimation and performance prediction.

Tokens have become the fundamental unit of economic value in the AI industry. Most AI service providers charge based on token consumption, with separate rates for input and output tokens. OpenAI’s pricing structure exemplifies this model: as of 2024, GPT-4 charges approximately $0.03 per 1,000 input tokens and $0.06 per 1,000 output tokens, meaning output tokens cost roughly twice as much as input tokens. This pricing structure reflects the computational reality that generating new tokens requires more processing power than processing existing input tokens. Claude’s pricing follows a similar pattern, while Perplexity and other platforms implement their own token-based pricing schemes.

Understanding token economics is crucial for managing AI costs at scale. A single verbose prompt might consume 500 tokens, while a concise, well-structured prompt accomplishes the same goal with only 200 tokens. Over thousands of API calls, this efficiency difference translates to significant cost savings. Research indicates that enterprises using AI-driven content monitoring tools can reduce token consumption by 20-40% through prompt optimization and intelligent caching strategies. Additionally, many platforms implement rate limits measured in tokens per minute (TPM), restricting how many tokens a user can process within a specific timeframe. These limits prevent abuse and ensure fair resource distribution across users. For organizations monitoring their brand presence in AI responses through platforms like AmICited, understanding token consumption patterns reveals not just cost implications but also the depth and breadth of AI engagement with your content.

For platforms dedicated to monitoring brand and domain appearances in AI responses, tokens represent a critical metric for measuring engagement and influence. When AmICited tracks how your brand appears in ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews, token counts reveal the computational resources these systems dedicate to your content. A citation that consumes 50 tokens indicates more substantial engagement than a brief mention consuming only 5 tokens. By analyzing token patterns across different AI platforms, organizations can understand which AI systems prioritize their content, how comprehensively different models discuss their brand, and whether their content receives deeper analysis or superficial treatment.

Token tracking also enables sophisticated analysis of AI response quality and relevance. When an AI system generates a lengthy, detailed response about your brand using hundreds of tokens, it indicates high confidence and comprehensive knowledge. Conversely, brief responses using few tokens might suggest limited information or lower relevance rankings. This distinction is crucial for brand management in the AI era. Organizations can use token-level monitoring to identify which aspects of their brand receive the most AI attention, which platforms prioritize their content, and how their visibility compares to competitors. Furthermore, token consumption patterns can reveal emerging trends—if token usage for your brand suddenly increases across multiple AI platforms, it may indicate growing relevance or recent news coverage that’s being incorporated into AI training data.

The tokenization landscape continues evolving as language models become more sophisticated and capable. Early language models used relatively simple word-level tokenization, but modern systems employ advanced subword tokenization methods that balance efficiency with semantic preservation. Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), pioneered by OpenAI and now industry-standard, represents a significant advancement over earlier approaches. However, emerging research suggests even more efficient tokenization methods may emerge as models scale to handle longer contexts and more diverse data types.

The future of tokenization extends beyond text. Multimodal models like GPT-4 Vision and Claude 3 tokenize images, audio, and video in addition to text, creating unified token representations across modalities. This expansion means a single prompt might contain text tokens, image tokens, and audio tokens, all processed through the same neural network architecture. As these multimodal systems mature, understanding token consumption across different data types becomes increasingly important. Additionally, the emergence of reasoning models that generate intermediate “thinking tokens” invisible to users represents another evolution. These models consume significantly more tokens during inference—sometimes 100x more than traditional models—to produce higher-quality reasoning and problem-solving. This development suggests the AI industry may shift toward measuring value not just by output tokens but by total computational tokens consumed, including hidden reasoning processes.

The standardization of token counting across platforms remains an ongoing challenge. While OpenAI’s tiktoken library has become widely adopted, different platforms maintain proprietary tokenizers that produce varying results. This fragmentation creates complexity for organizations monitoring their presence across multiple AI systems. Future developments may include industry-wide token standards, similar to how character encoding standards (UTF-8) unified text representation across systems. Such standardization would simplify cost prediction, enable fair comparison of AI services, and facilitate better monitoring of brand presence across the AI ecosystem. For platforms like AmICited dedicated to tracking brand appearances in AI responses, standardized token metrics would enable more precise measurement of how different AI systems engage with content and allocate computational resources.

+++

A token is the fundamental unit of text that language models process and understand. Tokens represent words, subwords, character sequences, or punctuation marks, each assigned a unique numerical identifier within the model’s vocabulary. Rather than processing raw text directly, AI systems like ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews convert all input text into sequences of tokens—essentially translating human language into a numerical format that neural networks can compute. This tokenization process is the critical first step that enables language models to analyze semantic relationships, generate coherent responses, and maintain computational efficiency. Understanding tokens is essential for anyone working with AI systems, as token counts directly influence API costs, response quality, and the model’s ability to maintain context across conversations.

Tokenization is the systematic process of breaking down raw text into discrete tokens that a language model can process. When you input text into an AI system, the tokenizer first analyzes the text and splits it into manageable units. For example, the sentence “I heard a dog bark loudly” might be tokenized into individual tokens: I, heard, a, dog, bark, loudly. Each token then receives a unique numerical identifier—perhaps I becomes token ID 1, heard becomes 2, a becomes 3, and so forth. This numerical representation allows the neural network to perform mathematical operations on the tokens, calculating relationships and patterns that enable the model to understand meaning and generate appropriate responses.

The specific way text is tokenized depends on the tokenization algorithm employed by each model. Different language models use different tokenizers, which is why the same text can produce varying token counts across platforms. The tokenizer’s vocabulary—the complete set of unique tokens it recognizes—typically ranges from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of tokens. When the tokenizer encounters text it hasn’t seen before or words outside its vocabulary, it applies specific strategies to handle these cases, either breaking them into smaller subword tokens or representing them as combinations of known tokens. This flexibility is crucial for handling diverse languages, technical jargon, typos, and novel word combinations that appear in real-world text.

Different tokenization approaches offer distinct advantages and trade-offs. Understanding these methods is essential for comprehending how various AI platforms process information differently:

| Tokenization Method | How It Works | Advantages | Disadvantages | Used By |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word-Level | Splits text into complete words based on spaces and punctuation | Simple to understand; preserves full word meaning; smaller token sequences | Large vocabulary size; cannot handle unknown or rare words (OOV); inflexible with typos | Traditional NLP systems |

| Character-Level | Treats every individual character as a token, including spaces | Handles all possible text; no out-of-vocabulary issues; fine-grained control | Very long token sequences; requires more computation; low semantic density per token | Some specialized models; Chinese language models |

| Subword-Level (BPE) | Iteratively merges frequent character/subword pairs into larger tokens | Balances vocabulary size and coverage; handles rare words effectively; reduces OOV errors | More complex implementation; may split meaningful units; requires training | GPT models, ChatGPT, Claude |

| WordPiece | Starts with characters and progressively merges frequent combinations | Excellent for handling unknown words; efficient vocabulary; good semantic preservation | Requires pre-training; more computationally intensive | BERT, Google models |

| SentencePiece | Language-agnostic method treating text as raw bytes | Excellent for multilingual models; handles any Unicode character; no preprocessing needed | Less intuitive; requires specialized tools | Multilingual models, T5 |

Once text is converted into tokens, language models process these numerical sequences through multiple layers of neural networks. Each token is represented as a multi-dimensional vector called an embedding, which captures semantic meaning and contextual relationships. During the training phase, the model learns to recognize patterns in how tokens appear together, understanding that certain tokens frequently co-occur or appear in similar contexts. For instance, the tokens for “king” and “queen” develop similar embeddings because they share semantic properties, while “king” and “paper” have more distant embeddings due to their different meanings and usage patterns.

The model’s attention mechanism is crucial to this process. Attention allows the model to weigh the importance of different tokens relative to each other when generating a response. When processing the sentence “The bank executive sat by the river bank,” the attention mechanism helps the model understand that the first “bank” refers to a financial institution while the second “bank” refers to a riverbank, based on contextual tokens like “executive” and “river.” This contextual understanding emerges from the model’s learned relationships between token embeddings, enabling sophisticated language comprehension that goes far beyond simple word matching.

During inference (when the model generates responses), it predicts the next token in a sequence based on all previous tokens. The model calculates probability scores for every token in its vocabulary, then selects the most likely next token. This process repeats iteratively—the newly generated token is added to the sequence, and the model uses this expanded context to predict the following token. This token-by-token generation continues until the model predicts a special “end of sequence” token or reaches the maximum token limit. This is why understanding token limits is critical: if your prompt and desired response together exceed the model’s context window, the model cannot generate a complete response.

Every language model has a context window—a maximum number of tokens it can process simultaneously. This limit combines both input tokens (your prompt) and output tokens (the model’s response). For example, GPT-3.5-Turbo has a context window of 4,096 tokens, while GPT-4 offers windows ranging from 8,000 to 128,000 tokens depending on the version. Claude 3 models support context windows up to 200,000 tokens, enabling analysis of entire books or extensive documents. Understanding your model’s context window is essential for planning prompts and managing token budgets effectively.

Token counting tools are essential for optimizing AI usage. OpenAI provides the tiktoken library, an open-source tokenizer that allows developers to count tokens before making API calls. This prevents unexpected costs and enables precise prompt optimization. For example, if you’re using GPT-4 with an 8,000-token context window and your prompt uses 2,000 tokens, you have 6,000 tokens available for the model’s response. Knowing this constraint helps you craft prompts that fit within available token space while still requesting comprehensive responses. Different models use different tokenizers—Claude uses its own tokenization system, Perplexity implements its own approach, and Google AI Overviews uses yet another method. This variation means the same text produces different token counts across platforms, making platform-specific token counting essential for accurate cost estimation and performance prediction.

Tokens have become the fundamental unit of economic value in the AI industry. Most AI service providers charge based on token consumption, with separate rates for input and output tokens. OpenAI’s pricing structure exemplifies this model: as of 2024, GPT-4 charges approximately $0.03 per 1,000 input tokens and $0.06 per 1,000 output tokens, meaning output tokens cost roughly twice as much as input tokens. This pricing structure reflects the computational reality that generating new tokens requires more processing power than processing existing input tokens. Claude’s pricing follows a similar pattern, while Perplexity and other platforms implement their own token-based pricing schemes.

Understanding token economics is crucial for managing AI costs at scale. A single verbose prompt might consume 500 tokens, while a concise, well-structured prompt accomplishes the same goal with only 200 tokens. Over thousands of API calls, this efficiency difference translates to significant cost savings. Research indicates that enterprises using AI-driven content monitoring tools can reduce token consumption by 20-40% through prompt optimization and intelligent caching strategies. Additionally, many platforms implement rate limits measured in tokens per minute (TPM), restricting how many tokens a user can process within a specific timeframe. These limits prevent abuse and ensure fair resource distribution across users. For organizations monitoring their brand presence in AI responses through platforms like AmICited, understanding token consumption patterns reveals not just cost implications but also the depth and breadth of AI engagement with your content.

For platforms dedicated to monitoring brand and domain appearances in AI responses, tokens represent a critical metric for measuring engagement and influence. When AmICited tracks how your brand appears in ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and Google AI Overviews, token counts reveal the computational resources these systems dedicate to your content. A citation that consumes 50 tokens indicates more substantial engagement than a brief mention consuming only 5 tokens. By analyzing token patterns across different AI platforms, organizations can understand which AI systems prioritize their content, how comprehensively different models discuss their brand, and whether their content receives deeper analysis or superficial treatment.

Token tracking also enables sophisticated analysis of AI response quality and relevance. When an AI system generates a lengthy, detailed response about your brand using hundreds of tokens, it indicates high confidence and comprehensive knowledge. Conversely, brief responses using few tokens might suggest limited information or lower relevance rankings. This distinction is crucial for brand management in the AI era. Organizations can use token-level monitoring to identify which aspects of their brand receive the most AI attention, which platforms prioritize their content, and how their visibility compares to competitors. Furthermore, token consumption patterns can reveal emerging trends—if token usage for your brand suddenly increases across multiple AI platforms, it may indicate growing relevance or recent news coverage that’s being incorporated into AI training data.

The tokenization landscape continues evolving as language models become more sophisticated and capable. Early language models used relatively simple word-level tokenization, but modern systems employ advanced subword tokenization methods that balance efficiency with semantic preservation. Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), pioneered by OpenAI and now industry-standard, represents a significant advancement over earlier approaches. However, emerging research suggests even more efficient tokenization methods may emerge as models scale to handle longer contexts and more diverse data types.

The future of tokenization extends beyond text. Multimodal models like GPT-4 Vision and Claude 3 tokenize images, audio, and video in addition to text, creating unified token representations across modalities. This expansion means a single prompt might contain text tokens, image tokens, and audio tokens, all processed through the same neural network architecture. As these multimodal systems mature, understanding token consumption across different data types becomes increasingly important. Additionally, the emergence of reasoning models that generate intermediate “thinking tokens” invisible to users represents another evolution. These models consume significantly more tokens during inference—sometimes 100x more than traditional models—to produce higher-quality reasoning and problem-solving. This development suggests the AI industry may shift toward measuring value not just by output tokens but by total computational tokens consumed, including hidden reasoning processes.

The standardization of token counting across platforms remains an ongoing challenge. While OpenAI’s tiktoken library has become widely adopted, different platforms maintain proprietary tokenizers that produce varying results. This fragmentation creates complexity for organizations monitoring their presence across multiple AI systems. Future developments may include industry-wide token standards, similar to how character encoding standards (UTF-8) unified text representation across systems. Such standardization would simplify cost prediction, enable fair comparison of AI services, and facilitate better monitoring of brand presence across the AI ecosystem. For platforms like AmICited dedicated to tracking brand appearances in AI responses, standardized token metrics would enable more precise measurement of how different AI systems engage with content and allocate computational resources.

On average, one token represents approximately 4 characters or roughly three-quarters of a word in English text. However, this varies significantly depending on the tokenization method used. Short words like 'the' or 'a' typically consume one token, while longer or complex words may require two or more tokens. For example, the word 'darkness' might be split into 'dark' and 'ness' as two separate tokens.

Language models are neural networks that process numerical data, not text. Tokens convert text into numerical representations (embeddings) that neural networks can understand and process efficiently. This tokenization step is essential because it standardizes input, reduces computational complexity, and enables the model to learn semantic relationships between different pieces of text through mathematical operations on token vectors.

Input tokens are the tokens from your prompt or question sent to the AI model, while output tokens are the tokens the model generates in its response. Most AI services charge differently for input and output tokens, with output tokens typically costing more because generating new content requires more computational resources than processing existing text. Your total token usage is the sum of both input and output tokens.

Token count directly determines API costs for language models. Services like OpenAI, Claude, and others charge per token, with rates varying by model and token type. A longer prompt with more tokens costs more to process, and generating longer responses consumes more output tokens. Understanding token efficiency helps optimize costs—concise prompts that convey necessary information minimize token consumption while maintaining response quality.

A context window is the maximum number of tokens a language model can process at once, combining both input and output tokens. For example, GPT-4 has a context window of 8,000 to 128,000 tokens depending on the version. This limit determines how much text the model can 'see' and remember when generating responses. Larger context windows allow processing longer documents, but they also require more computational resources.

The three primary tokenization methods are: word-level (splitting text into complete words), character-level (treating each character as a token), and subword-level tokenization like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) used by GPT models. Subword tokenization is most common in modern LLMs because it balances vocabulary size, handles rare words effectively, and reduces out-of-vocabulary (OOV) errors while maintaining semantic meaning.

For platforms like AmICited that monitor AI responses across ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, and Google AI Overviews, token tracking is crucial for understanding how much of your brand content or URLs are being processed and cited by AI systems. Token counts reveal the depth of AI engagement with your content—higher token usage indicates more substantial citations or references, helping you measure your brand's visibility and influence in AI-generated responses.

Yes, absolutely. Different language models use different tokenizers and vocabularies, so the same text will produce different token counts. For example, the word 'antidisestablishmentarianism' produces 5 tokens in GPT-3 but 6 tokens in GPT-4 due to different tokenization algorithms. This is why it's important to use model-specific token counters when estimating costs or planning prompts for particular AI systems.

Start tracking how AI chatbots mention your brand across ChatGPT, Perplexity, and other platforms. Get actionable insights to improve your AI presence.

Explore how token limits affect AI performance and learn practical strategies for content optimization including RAG, chunking, and summarization techniques.

Learn how AI models process text through tokenization, embeddings, transformer blocks, and neural networks. Understand the complete pipeline from input to outpu...

Learn how to optimize content readability for AI systems, ChatGPT, Perplexity, and AI search engines. Discover best practices for structure, formatting, and cla...